Source: The Guardian - Monday 24 June 2013

At school I was the outsider, the odd one, the word-blind child who didn't fit in. I lived in my head – a dreamer, a dyslexic teenager, a round peg in a square hole who was told I would be lucky to get any qualifications, let alone a job. My education was a comedy of errors. It took place in the era of those two-dimensional technicolour children, Janet and John. Janet and John were my nightmare, a reading scheme that I couldn't get out of, which I was forced to stay on until the age of 11, getting no further than "Janet and John had a ball."

I can definitely assure you that not one of us had a ball. Not them, not me. If it hadn't been for my imagination and my ability to dream my way out of the narrow confines of Janet and John and their ball, I would have proved Miss Bell right and probably ended up working in a supermarket, which would have been a disaster, because I was no better at maths than I was at reading.

Schools back then didn't know about dyslexia. All I knew was that I wasn't like everyone else, and that made me stupid. Today I see that Janet and John have grown up – John advises Michael Gove on his education policy, while Janet works for Ofsted, enjoying the terror her department can bring to schools and teachers alike. Both Janet and John agree with Gove that learning by rote (or by rope, as I call it, the gallows for the inquiring mind) is the only answer. Cut down on creativity, give the little blighters exams, exams, exams until they all become good sheep.

I eventually ended up in a school for maladjusted children, because no other school that would take me. I suppose this was the equivalent of what would now be a school for kids with Asbos. I had been classified as "unteachable", but at the age of 14, when everyone had given up hope, I learned to read. The first book I read was Wuthering Heights, and after that no one could stop me. My mother said that if I got five O-levels I could go to art school and, much to my teachers' chagrin, I did just that.

Dyslexia is not a disability – it's a gift. It means that I, and many other dyslexic thinkers can portray the world through images because we think in images. I can build worlds, freeze the frame, walk around and touch. I can read people's faces, drawings, buildings, landscapes and all things in the visual world more quickly than many of my non-dyslexic friends. I paint with words; they are my colours.

Non-dyslexic people often challenge my dyslexia – they don't believe I write my books, or they think I have a ghost writer. Many dyslexic people also look at me with doubt – how do I do it? A published author can't possibly be severely dyslexic. Many of them have been made to think there's no point in trying to be a writer, even if that's what they passionately want to be. The key is not to listen to what they are told. If I had listened I wouldn't have become a writer.

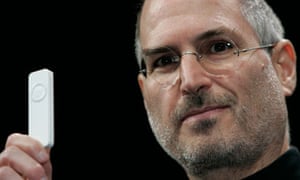

I do think there really need to be more publicly dyslexic role models for children and adults today. Lots of famous dyslexics are not open about it. Richard Branson has never proudly claimed his dyslexia, nor did Steve Jobs; Keira Knightley is more open about it. Then there are my personal favourites: F Scott Fitzgerald, Agatha Christie, John Lennon and Einstein – who said: "Imagination is more important than knowledge." These are what I call "outside the box" thinkers, and never has there been a time, with the technology we have, and the world in the muddled up state it is in, when we have had more need to be thinking outside the box.

Happily, over the past two years, I've gradually been seeing people open up to and become more interested in the contradictions that are associated with being a dyslexic novelist. After all, you can spell every word in the dictionary and know every grammatical rule in the world, but this does not make you a writer, nor does it give you an imagination; an imagination is something quite unique to every individual and it needs to be treasured.

No comments:

Post a Comment